Mongabay: India: Sunday, 31 March 2024.

But unpredictable weather, over the past five years, has disrupted this schedule, said Shamji Kangad, owner of Neelkanth Salt and Supply Private Ltd, which operates marine salt works in the Kachchh and Bharuch districts of Gujarat.

The salt production is mainly done by people who belong to the Agariya community, the salt farmers of Kachchh. “All Agariyas go back to their villages on Ashadi Beej. But lately, the monsoon has been delayed, sometimes even by up to a month. The rain that usually ends around September earlier, now extends up to November sometimes. We are still adjusting to this shift,” said Kangad.

Cyclones, Tauktae in May 2021 and Biparjoy in June 2023, also terminated the salt production season early. “Although the cyclone warning is only for ten days, it ends up disrupting the production cycle for 30 days as the salt pans have to be emptied and then repair work has to be taken up. By then, the monsoon starts. So, we lose the peak summer season when maximum solar evaporation happens,” said Kangad. “These two cyclones resulted in a 25% loss of production,” said Chetan Kamdar, owner of the Bhavnagar Salt and Industrial Works Pvt. Ltd. in the Bhavnagar district of the state.

“The season has reduced from nine months to six months, bringing down salt production to 60-70% in the coastal belt,” claimed Bachchu Bhai Ahir, President of the Gandhidham-based Kutch Small Scale Salt Manufacturers Association. “But there is no scarcity. Many new areas are coming under salt production and the overall production from Gujarat will remain the same,” Ahir added.

After China and the U.S., India is the world’s third-largest producer of salt. Four states, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, parts of Andhra Pradesh, and Rajasthan, fulfill most of India’s salt needs. Of the total salt production from these states, more than 80% comes from Gujarat.

Increasing climate variations in recent years have shortened the salt production season and are forcing this large but unorganised sector to increase production in a limited time period. “Salt is not produced in factory sheds. Most of the production happens near the coast, so global warming is affecting industry worldwide. In India, average production has come down from 30 million tonnes (MT) from 2016 to 27-28 MT to 2022. In China, it also came down from 69 to 53 MT since 2012, and despite being the biggest producer of salt, China imports from India,” said Bharat Rawal, president of the Indian Salt Manufacturers Association (ISMA), Ahmedabad.

The situation is similar in Tamil Nadu as well. Unseasonal floods in the state in December 2023 washed off four lakh (400,000) tonnes of salt in Thoothukudi (formerly Tuticorin). “It rained more than 90 cm in 24 hours on December 17-18. Silt deposited on the entire salt works. To remove silt itself will take more than six months and then more time to prepare the salt pans again and recrystallise,” said Arulraj Solomon C., of the Thoothukudi Small Scale Salt Manufacturers Association, at a conference on salt and marine chemicals, in February this year.

Essential conditions for an essential commodity

Sea salt constitutes about 82% of the total salt production in the country and Gujarat significantly contributes to the total production. The state produced 25 MT of sea salt in the year 2023 of the country’s total production of 30.8 MT.

The salt is mainly made on the many salt works along the 1600 km long coastline of the state as well as in sub-soil brine reserves in a few areas. After monsoon, seawater from creeks is lifted via bulk pumps and routed through a series of hardened flat beds (sometimes up to 90 pans), where it gradually evaporates in the sun, increasing the brine’s concentration from 3 to 4 degrees on the Baumé scale (a measure to calculate salt concentration) to 25 degrees Baumé. At this stage, it is shifted to the final pan, known as the crystalliser, where it solidifies. This raw salt, called “karkach”, is sold as it is or further cleaned up. Salt for edible purposes needs to be cleaned of mud, while that for industrial purposes needs to get rid of calcium and magnesium.

Normally, about 10% salt is lost in washing. During winters, since evaporation is low, salt is collected once a month, but in summers, it is collected every 20 days, said Kangad.

According to scientists at Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute (CSMCRI), an institute under the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research of the Government, ideal weather conditions for salt production include an average temperature range of 20 to 45 degrees Celsius, rainfall not exceeding 600 mm in a total spell of 100 days, relative humidity of 50 to 70%, wind velocity of 3 to 15 kms per hour, wind direction from North-East to South-West and North-West to South-West that aids evaporation of brine.

“Dry weather, along with clay soil (that reduces brine seepage), unlike the sandy beaches of eastern India and flat land because of the two Gulfs, Kachchh and Cambay that provided enough space for solar evaporation, made Gujarat ideal for salt production. Except soil, everything is changing now,” said Rawal of ISMA.

Citing weather data from the local airport, salt manufacturer Kamdar, said that the average rainfall from 2019 to 2023 in Bhavnagar has consistently been around 1000 mm, which is against the normal rainfall of 600 mm in the Bhavnagar district. “The number of rainy days has gone up from 30 to 78 in the last few years, and this year, it was 100 days of rainfall. In Kachchh, annual rainfall has been above 600 mm as compared to the normal 450 mm since the last four years, with this year being the highest at 730 mm,” said Kamdar. “In a normal season, I get a production of four lakh (400,000) tonnes per annum, but there has been no normal season for at least two years. Unseasonal rain at the time of salt harvest dilutes the brine in the crystalliser as well as the salt concentration in seawater. High winds during cyclones cause washing area sheds and other machinery to break down,” he said.

Scientists attribute unseasonal rain to increasing sea-surface temperature. “As temperature rises, there is more evaporation of seawater, resulting in highly saturated air mass over salt works in coastal areas. This increases humidity, which in turn lowers the evaporation of salt,” said Bhoomi R. Andharia, Senior Scientist at the Salt and Marine Water Division of CSMCRI.

According to a 2023 study, the Arabian Sea has “experienced dramatic surface (1.2–1.4 °C) and subsurface (1.4 °C) warmings in recent years compared to earlier decades. This enhanced warming is likely enhancing the convective activity over the Arabian Sea, which favours the formation and intensification of tropical cyclones in recent decades.” Another study says that there has been a 52% increase in the number of cyclonic storms over the Arabian Sea from 2001 to 2019 compared to 1982 to 2000.

Low pressure and high velocity wind events are regular in this belt but no massive damage on the scale of Tauktae and Biparjoy ever took place before this, said Kamdar. Another salt manufacturer, Kangad, however, said that the 1998 Gujarat cyclone saw huge damage and 23 workers at his marine salt works were swept away in the cyclone. “That was due to unpreparedness. The warning systems were not in place then,” he said.

A 2013 study on rainfall noted that over a span of 30 years between 1983 and 2013, the average rainfall in the Saurashtra and Kachchh regions of the state, which have the maximum salt works in the state, has almost doubled from 378 mm to 674 mm.

Demand and supply

Salt is produced for edible, export and industrial (for the chlor-alkali industry to produce caustic soda, chlorine and soda ash) purposes. Demand has been rising in all three spheres. “Till 2004, we were only exporting to neighbouring countries with whom India had a treaty for supply, such as Nepal. But from 2012 to now, exports have gone up from 3.4 MT to above 100 MT. Even China sources salt from India for its industrial needs,” said Rawal.

Exports have gone up because of advanced loading infrastructure, said Kangad. “Earlier, the demurrage cost us more than the price of salt. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for sanitisers and other cleaning agents that need salt as raw material has also increased. With refined salt becoming popular, the consumption of edible salt has also gone up,” said Kangad. According to ISMA’s Rawal, if 6% of the edible salt was refined earlier (apart from being iodised), now 50% of it is being refined. Refining accounts for 20% of washing losses.

As per the 2022-23 annual report of the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the total land under salt in the country is 6.57 lakh (657,000) acres. However, more land has recently been leased for salt production in the Greater Rann of Kutch, also called the White Rann, due to its extensive salt deposits. Of seven new salt works in this region, two companies are directly exporting natural salt extracted from these deposits, while the rest are using the same technique of pumping brine and evaporating it in solar ponds. “If the season is good, there will easily be a production of 30-40 million tonnes from Gujarat this year. So even as the coastal salt production is going down, there is no reason to worry,” said Kangad.

There is a surge in prices of both edible and industrial salt. Market prices of a kilogram of edible salt have gone up from Rs. 15 to Rs. 25 per kgsince 2016, said a wholesale grocery dealer in Nangal, Punjab. “From Rs. 600 to Rs. 700 per tonne in 2016, the salt price has gone up to Rs. 900 to Rs. 1000 per tonne now,” said Ahir. In the Little Rann of Kutch (LRK) belt, where salt is made from subsoil brine, rates doubled from Rs. 300 to Rs. 610 per tonne from 2021 to 2023, informed Hingor Rabari, a salt trader in Kharagoda in Surendranagar district. “More refineries are also coming up here. Seeing good profit, more people are getting into raw salt production in the LRK region,” said Rabari.

“We have seen days when salt production cost us Rs. 500 and it was sold at Rs. 300. Agariyas had to throw their salt and were committing suicides. But now that the rates have gone up, the chlor-alkali industry is panicking about prices even though salt is just Rs. 3000 out of their Rs. 20,000 per tonne cost of production,” said Kangad.

Adapting to climate impacts

To increase production during the limited salt season, Andharia at CMSRI and her team are working on technological solutions such as reverse pumping brine from the crystalliser to the condenser as a damage control measure against rainfall. The team is also exploring evaporation-enhancing techniques such as mechanical turbulation, heat exchange with the help of solar panels and using chemical dyes that increase brine temperature and aid evaporation. “Crystalliser area is usually 1/10th of the total salt works. That needs to be increased now depending on the total rainfall. The rain makes the soil loose and percolation in the crystaliser leads to loss of salt. Mechanised operations also cannot take place as the soft soil can’t take the load of heavy machinery. Hardening of beds with a geo-polymer sheet helps. It will also aid in quality improvement as no mud will mix with salt, thereby reducing washing losses,” said Andharia.

According to Rawal, the government needs to take ownership of this essential commodity. “There was a Salt Commissioner’s Office, but it is also on the verge of being shut down. There is no active regulatory body to oversee production, supply, and even areas under salt production as of today. There is a crisis in the making if the government disowns its responsibility,” he said. “Secondly, salt needs to be categorised as an agricultural commodity and not a mined mineral as it is farmed just like crops. In pre-partition India, salt was sourced from rock deposits in Sind and from the hills of Mandi in Himachal Pradesh. Since then, salt continues to be counted as a mineral even though only 0.5% of it now comes from the hills,” said Rawal.

- Gujarat produces 80% of India’s salt. Most of it is produced in coastal areas which are impacted by unpredictable rainfall and cyclones.

- As production in coastal salt works has reduced, and demand for edible and industrial salt as well as exports has increased, prices have gone up. Salt manufacturers, however, say that there is no scarcity as new areas are coming under salt production.

- Long-standing salt producers say that an active government authority should regulate the salt industry as it is an essential commodity.

- The Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute is actively pursuing several technological solutions, to deal with a shortened salt production season impacted by erratic weather.

But unpredictable weather, over the past five years, has disrupted this schedule, said Shamji Kangad, owner of Neelkanth Salt and Supply Private Ltd, which operates marine salt works in the Kachchh and Bharuch districts of Gujarat.

The salt production is mainly done by people who belong to the Agariya community, the salt farmers of Kachchh. “All Agariyas go back to their villages on Ashadi Beej. But lately, the monsoon has been delayed, sometimes even by up to a month. The rain that usually ends around September earlier, now extends up to November sometimes. We are still adjusting to this shift,” said Kangad.

Cyclones, Tauktae in May 2021 and Biparjoy in June 2023, also terminated the salt production season early. “Although the cyclone warning is only for ten days, it ends up disrupting the production cycle for 30 days as the salt pans have to be emptied and then repair work has to be taken up. By then, the monsoon starts. So, we lose the peak summer season when maximum solar evaporation happens,” said Kangad. “These two cyclones resulted in a 25% loss of production,” said Chetan Kamdar, owner of the Bhavnagar Salt and Industrial Works Pvt. Ltd. in the Bhavnagar district of the state.

“The season has reduced from nine months to six months, bringing down salt production to 60-70% in the coastal belt,” claimed Bachchu Bhai Ahir, President of the Gandhidham-based Kutch Small Scale Salt Manufacturers Association. “But there is no scarcity. Many new areas are coming under salt production and the overall production from Gujarat will remain the same,” Ahir added.

After China and the U.S., India is the world’s third-largest producer of salt. Four states, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, parts of Andhra Pradesh, and Rajasthan, fulfill most of India’s salt needs. Of the total salt production from these states, more than 80% comes from Gujarat.

Increasing climate variations in recent years have shortened the salt production season and are forcing this large but unorganised sector to increase production in a limited time period. “Salt is not produced in factory sheds. Most of the production happens near the coast, so global warming is affecting industry worldwide. In India, average production has come down from 30 million tonnes (MT) from 2016 to 27-28 MT to 2022. In China, it also came down from 69 to 53 MT since 2012, and despite being the biggest producer of salt, China imports from India,” said Bharat Rawal, president of the Indian Salt Manufacturers Association (ISMA), Ahmedabad.

The situation is similar in Tamil Nadu as well. Unseasonal floods in the state in December 2023 washed off four lakh (400,000) tonnes of salt in Thoothukudi (formerly Tuticorin). “It rained more than 90 cm in 24 hours on December 17-18. Silt deposited on the entire salt works. To remove silt itself will take more than six months and then more time to prepare the salt pans again and recrystallise,” said Arulraj Solomon C., of the Thoothukudi Small Scale Salt Manufacturers Association, at a conference on salt and marine chemicals, in February this year.

Essential conditions for an essential commodity

Sea salt constitutes about 82% of the total salt production in the country and Gujarat significantly contributes to the total production. The state produced 25 MT of sea salt in the year 2023 of the country’s total production of 30.8 MT.

The salt is mainly made on the many salt works along the 1600 km long coastline of the state as well as in sub-soil brine reserves in a few areas. After monsoon, seawater from creeks is lifted via bulk pumps and routed through a series of hardened flat beds (sometimes up to 90 pans), where it gradually evaporates in the sun, increasing the brine’s concentration from 3 to 4 degrees on the Baumé scale (a measure to calculate salt concentration) to 25 degrees Baumé. At this stage, it is shifted to the final pan, known as the crystalliser, where it solidifies. This raw salt, called “karkach”, is sold as it is or further cleaned up. Salt for edible purposes needs to be cleaned of mud, while that for industrial purposes needs to get rid of calcium and magnesium.

Normally, about 10% salt is lost in washing. During winters, since evaporation is low, salt is collected once a month, but in summers, it is collected every 20 days, said Kangad.

According to scientists at Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute (CSMCRI), an institute under the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research of the Government, ideal weather conditions for salt production include an average temperature range of 20 to 45 degrees Celsius, rainfall not exceeding 600 mm in a total spell of 100 days, relative humidity of 50 to 70%, wind velocity of 3 to 15 kms per hour, wind direction from North-East to South-West and North-West to South-West that aids evaporation of brine.

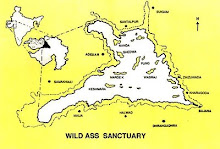

“Dry weather, along with clay soil (that reduces brine seepage), unlike the sandy beaches of eastern India and flat land because of the two Gulfs, Kachchh and Cambay that provided enough space for solar evaporation, made Gujarat ideal for salt production. Except soil, everything is changing now,” said Rawal of ISMA.

Citing weather data from the local airport, salt manufacturer Kamdar, said that the average rainfall from 2019 to 2023 in Bhavnagar has consistently been around 1000 mm, which is against the normal rainfall of 600 mm in the Bhavnagar district. “The number of rainy days has gone up from 30 to 78 in the last few years, and this year, it was 100 days of rainfall. In Kachchh, annual rainfall has been above 600 mm as compared to the normal 450 mm since the last four years, with this year being the highest at 730 mm,” said Kamdar. “In a normal season, I get a production of four lakh (400,000) tonnes per annum, but there has been no normal season for at least two years. Unseasonal rain at the time of salt harvest dilutes the brine in the crystalliser as well as the salt concentration in seawater. High winds during cyclones cause washing area sheds and other machinery to break down,” he said.

Scientists attribute unseasonal rain to increasing sea-surface temperature. “As temperature rises, there is more evaporation of seawater, resulting in highly saturated air mass over salt works in coastal areas. This increases humidity, which in turn lowers the evaporation of salt,” said Bhoomi R. Andharia, Senior Scientist at the Salt and Marine Water Division of CSMCRI.

According to a 2023 study, the Arabian Sea has “experienced dramatic surface (1.2–1.4 °C) and subsurface (1.4 °C) warmings in recent years compared to earlier decades. This enhanced warming is likely enhancing the convective activity over the Arabian Sea, which favours the formation and intensification of tropical cyclones in recent decades.” Another study says that there has been a 52% increase in the number of cyclonic storms over the Arabian Sea from 2001 to 2019 compared to 1982 to 2000.

Low pressure and high velocity wind events are regular in this belt but no massive damage on the scale of Tauktae and Biparjoy ever took place before this, said Kamdar. Another salt manufacturer, Kangad, however, said that the 1998 Gujarat cyclone saw huge damage and 23 workers at his marine salt works were swept away in the cyclone. “That was due to unpreparedness. The warning systems were not in place then,” he said.

A 2013 study on rainfall noted that over a span of 30 years between 1983 and 2013, the average rainfall in the Saurashtra and Kachchh regions of the state, which have the maximum salt works in the state, has almost doubled from 378 mm to 674 mm.

Demand and supply

Salt is produced for edible, export and industrial (for the chlor-alkali industry to produce caustic soda, chlorine and soda ash) purposes. Demand has been rising in all three spheres. “Till 2004, we were only exporting to neighbouring countries with whom India had a treaty for supply, such as Nepal. But from 2012 to now, exports have gone up from 3.4 MT to above 100 MT. Even China sources salt from India for its industrial needs,” said Rawal.

Exports have gone up because of advanced loading infrastructure, said Kangad. “Earlier, the demurrage cost us more than the price of salt. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for sanitisers and other cleaning agents that need salt as raw material has also increased. With refined salt becoming popular, the consumption of edible salt has also gone up,” said Kangad. According to ISMA’s Rawal, if 6% of the edible salt was refined earlier (apart from being iodised), now 50% of it is being refined. Refining accounts for 20% of washing losses.

As per the 2022-23 annual report of the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the total land under salt in the country is 6.57 lakh (657,000) acres. However, more land has recently been leased for salt production in the Greater Rann of Kutch, also called the White Rann, due to its extensive salt deposits. Of seven new salt works in this region, two companies are directly exporting natural salt extracted from these deposits, while the rest are using the same technique of pumping brine and evaporating it in solar ponds. “If the season is good, there will easily be a production of 30-40 million tonnes from Gujarat this year. So even as the coastal salt production is going down, there is no reason to worry,” said Kangad.

There is a surge in prices of both edible and industrial salt. Market prices of a kilogram of edible salt have gone up from Rs. 15 to Rs. 25 per kgsince 2016, said a wholesale grocery dealer in Nangal, Punjab. “From Rs. 600 to Rs. 700 per tonne in 2016, the salt price has gone up to Rs. 900 to Rs. 1000 per tonne now,” said Ahir. In the Little Rann of Kutch (LRK) belt, where salt is made from subsoil brine, rates doubled from Rs. 300 to Rs. 610 per tonne from 2021 to 2023, informed Hingor Rabari, a salt trader in Kharagoda in Surendranagar district. “More refineries are also coming up here. Seeing good profit, more people are getting into raw salt production in the LRK region,” said Rabari.

“We have seen days when salt production cost us Rs. 500 and it was sold at Rs. 300. Agariyas had to throw their salt and were committing suicides. But now that the rates have gone up, the chlor-alkali industry is panicking about prices even though salt is just Rs. 3000 out of their Rs. 20,000 per tonne cost of production,” said Kangad.

Adapting to climate impacts

To increase production during the limited salt season, Andharia at CMSRI and her team are working on technological solutions such as reverse pumping brine from the crystalliser to the condenser as a damage control measure against rainfall. The team is also exploring evaporation-enhancing techniques such as mechanical turbulation, heat exchange with the help of solar panels and using chemical dyes that increase brine temperature and aid evaporation. “Crystalliser area is usually 1/10th of the total salt works. That needs to be increased now depending on the total rainfall. The rain makes the soil loose and percolation in the crystaliser leads to loss of salt. Mechanised operations also cannot take place as the soft soil can’t take the load of heavy machinery. Hardening of beds with a geo-polymer sheet helps. It will also aid in quality improvement as no mud will mix with salt, thereby reducing washing losses,” said Andharia.

According to Rawal, the government needs to take ownership of this essential commodity. “There was a Salt Commissioner’s Office, but it is also on the verge of being shut down. There is no active regulatory body to oversee production, supply, and even areas under salt production as of today. There is a crisis in the making if the government disowns its responsibility,” he said. “Secondly, salt needs to be categorised as an agricultural commodity and not a mined mineral as it is farmed just like crops. In pre-partition India, salt was sourced from rock deposits in Sind and from the hills of Mandi in Himachal Pradesh. Since then, salt continues to be counted as a mineral even though only 0.5% of it now comes from the hills,” said Rawal.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)